HMS Tanatside: Commanding Officers and War service

At the time of writing, there have been three Commanding Officers that have been identified as commanding HMS Tanatside, namely Lt.Cdr (Lieutenant Commander) Frank David Brown, RN, Cdr (Commander) Bernard Jasper de St. Croix, RN and A/Lt.Cdr (Acting Lieutenant Commander) Harry Hutchinson, RN. They commanded the Tanatside from 18th July 1942 to 21st December 1943, 21st December 1943 to 17 April 1945 and 17 April 1945 to late 1945 respectively.

Lieutenant Commander Frank David Brown, RN

Unfortunately there is no picture of Frank Brown but there is some personal information on him. He was born on the 21st June 1907 and served as an officer from 1st September 1927 as an Acting Sub Lieutenant and retiring as a Commander on the 21 June 1952. The Tanatside was his only command during the Second World War and he was Mentioned in Despatches twice. Mentioned in Despatches (MID for short) is when a soldier whose name appears in an official report that is written by a superior officer to High Command that describes the soldier’s gallantry or other commendable service in action against the enemy. He received these on the 11th November 1941 and 2 December 1941, most likely helping him to get the Command of the Tanatside. The medal itself is a single bronze oak leaf which was used from 1920 to 1993 and regardless of how many Mentions, only one such decoration was worn.

Commander Bernard Jasper de St. Croix

Unlike the first Captain (in Navy Etiquette, whoever is in Command and under the rank of Captain is also referred to as Captain informally while on ship), a picture is available of Bernard de St. Croix. He was born on the 28th August 1903 and was son of Frederick Alexander de St. Croix (1862-1921) and Lucy Elizabeth Tuck (1877-1914). He was married on the 29th June 1925 to Helenora Margaret Stehn and they had one son and one daughter. He died on the 20th February 1965 and buried at St. Andrew’s Church, Bishopstone nr Seaford. They also have a family website to find out more and I thank them for this information and Bernard de St. Croix service.

He achieved the rank of Commander on the 31st December 1939 and was the commander of the HMS Aberdeen, HMS Salisbury and HMS Tanatside. It was when he was in command of the Tanatside that he got two decorations; he was Mentioned in Despatches on the 28th November 1944 and the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) on the 19th December 1944. The Distinguished Service Cross was awarded for those who demonstrated "... gallantry during active operations against the enemy at sea." (cite Uboat.net) The Mention in Despatches was awarded due to the role of the Tanatside in Operation Neptune, more commonly known as D-Day and this role will be discussed later. The Distinguished Service Cross was given for successful action with enemy light forces. He finally retired on the 22nd October 1952 after being found medically unfit for duty.

Lieutenant Commander Harry Hutchinson

Lt.C Hutchinson was the last Captain/Commanding Officer of HMS Tanatside in her final, but relatively uneventful last year before being transferred to Greece in 1946 as part of the Royal Hellenic Navy and renamed Adrias. However, little is known about him apart from the fact he became a Lieutenant on the 16th August 1937 and becoming Lieutenant Commander on the same day and month in 1945, after taking command of the Tanatside. In addition, he retired on the 5th November 1953, having also commanded HMS Ambuscade and HMS Caistor Castle, which were a Destroyer and Corvette respectively.

War Service

HMS Tanatside did not have the most glamorous of starts. While her first set of trials at Scapa Flow with HMS Quality (Q Class destroyer) and HMS H 34 (Class H Submarine) as well as a practice attack on HMS Bermuda went fine on the 18th September 1942, on the day she did another set of trials, 26th September of the same year, she was damaged in a collision with an Allied vessel. The ship “sustained structural damage” in the collision with HM Minesweeper Bramble and two days later was taken in hand to repair in the Tyne shipyard. Once she was repaired and the work-up completed, she joined the Flotilla at Plymouth to intercept enemy coastal traffic and the defence of convoys in November of the same year. She then successfully participated in Operation Tunnel alongside HMS Sloop Egret for interception of a German tanker in December, intercepting it on the 12th, but the tanker, named Germania, was scuttled by her crew, probably to avoid capture of her resources.

In 1943, the ship remained on channel convoy defence and patrol deployment with the Flotilla, participating in training exercises, escorting the HMS Malaya but did again collide with the SS Normanville, sustaining damage to the forward structure. Despite her uneventful past, 1944 was the pinnacle of HMS Tanatside’s career. In February, 1944, she was in action against enemy forces, the German Torpedo Boat T29 and the minesweepers M156 and M206 with her sister ships, HMS Wensleydale, HMS Talybont and a Type-4 Hunt Class destroyer, HMS Brissenden off the coast of Brittany. The M156 was heavily damaged and later destroyed by British Hawker Typhoons with the Tanatside sustaining only slight damage in the exchange of fire with the Torpedo Boat.

Only a few months later, April 17th, HMS Tanatside started its participation in Operation Maple, a series of mine laying operations intended to provide protection for the cross Channel convoys from R boats and E boats (multi-purpose minesweepers and fast attack craft) during the later Operation Neptune, known as the D-Day landings. The Tanatside was first deployed alongside HM Escort Destroyer Melbreak and Motor Torpedo Boats to support HM Cruiser Apollo during minelaying operations. Two days later, both the Tanatside and the Melbreak, along with the Royal Navy destroyers Wensleydale, Haida (Royal Canadian Navy, RCN) and Ashanti to cover mine laying by the 10th Motor Launch Flotilla and the escorting of Motor Torpedo Boats off the French coast. On the 25th, she continued her charge in covering the 10th Motor Launch Flotilla with her sister ship, the Wensleydale. She took some fire from shore defensive batteries but sustained no damage.

In May, she was nominated with HMS Talybont and HMS Melbreak for duty with the Western Task Force in Force O under US Navy Command for the upcoming Normandy landings and commenced exercises for the largest naval landings in history. On the 6th of June, she arrived on Omaha beach with 18 other vessels in support of Operation Neptune - a mixture of American, French and British vessels, consisting of 2 Battleships, 4 Light Cruisers and 12 Destroyers as part of the bombardment fleet for Omaha beach.

The Tanatside was on the East side of Omaha beach, in the lead near the Fox Green sector supporting the American 1st Infantry Division in its assault on the fortifications there. From there, she was assigned alongside seven other vessels for interception patrols in defence of cross Channel routes against attack by E-Boats, later being released back to Flotilla duties. After a refit and trials, she re-joined the Flotilla at Plymouth, later being deployed in with the 21st Destroyer Flotilla in the North Sea area. In mid-December, she sustained major structural damage in its front in a collision with HM Frigate Byron.

In the final year of the war and after repairs, the Tanatside was again deployed with the Flotilla for interception patrols and convoy defence before becoming nominated for service in the Eastern Fleet after a refit. However, the refit was not completed and she was just maintained while berthed in Taranto until 1946. This is when she was transferred on loan to the Royal Hellenic Navy (Greece), taking the name Adrias but returning in 1962 to be demolished. The ceremony of the transfer from the British Royal Navy to the Greek Hellenic Navy consisted of a guard of 25 ranks and band at the request of Captain D Malta.

Blog by Max Bates

References and thanks to;

Cambrian News archive in Archifdy Ceredigion Archives, Aberystwyth

Uboat.net

Naval-history.net

Omaha Beach: A flawed Victory by Adrian Lewis. Page 227

Destroyers at Normandy: Naval Gunfire Support at Omaha Beach:

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/destroyers-at-normandy.html

Forces War Records.co.uk

https://www.unithistories.com/

Forgotten Fights: The Taking of WN61, Omaha Beach Fox Green Sector: https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/wn61-omaha-beach-fox-green-sector

Imperial War Museum

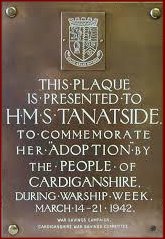

History Today: Warship Weeks

P. Boniface for his book H.M.S Superb which contained some information on the Tanatside.

Royal Naval Museum: http://www.royalnavalmuseum.org/info_sheets_Warshipweeks.html